In the first part of the series, we explored the standards of various states of play when we dove into traditional gaming and play to earn. The piece can be read here. This piece takes these two concepts further, exploring not only the financial models behind gaming but also the more experimental side of things.

Play And Earn

An iteration of the Play To Earn model, where earning is not the main priority for the player to engage with the game, but rather it acts as an addition to their time spent within the virtual space. In this manner, P&E is more similar to the Traditional Gaming model and the Freemium model. While it can stumble upon similar problems that Play To Earn encounters, the pressure on the “Earn” factor is much lower, hence the expectations of the Play And Earn type of player are different than Play To Earn. The “To Earner” will come mainly for the monetary rewards, while the “And Earner” can engage with the title because they are the King Of Their Hill, Thrill Seeker or a Networker kind of player that would be happy to get monetary compensation for his/hers in-game time.

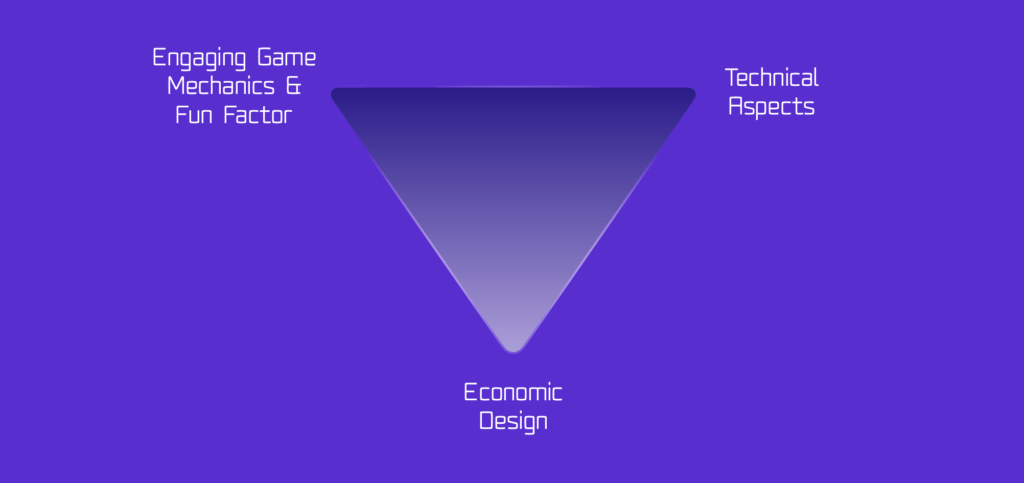

Economic design or technical work shouldn’t be in the spotlight in Play And Earn titles, but there should be a much higher focus on the mythical “fun” factor and engaging game mechanics:

Examples of titles that can belong to this group include:

- Legends Of Elysium – A card game where players will gain access to free basic decks.

- Blankos Block Party – Open-world multiplayer game with digital vinyl toys.

- Angrymals – A mobile game that is free to play but buying an NFT gives the player access to Play And Earn option.

Play to experiment

A model that involves various types of experimentation, ranging from graphics to economy systems (all from the developers’ side), to exploiting glitches (from the players’ side). It is crucial to note that the titles do not have to experiment in an uncompromising way – single elements or attempts of experimentation should be a factor in categorising a game title in such a way. Players can also engage in potentially mainstream titles to experiment in their own way – discovering the glitches or taking the game mechanics to the limits (which can include trial and error methods with informal currencies). Crucial to note here is that experimentation involves also wide tests on tokenomics

Examples of games that can belong to the experimental title group can include:

- Dark Forest – Ethereum-based real-time strategy that can be experienced in many different ways (which is recommended by the games’ Wiki: “If you are not a competitive player. Some players like to explore, some players like to build plugins, and some players like to explore and collect artifacts.”).

- Vib Ribbon – a rhythm video game where the player could use his or hers music CDs. It was also notable for its distinctive art style consisting of simple vector graphics.

- AIFA Football – The game that takes a new spin on AI usage. The creators (Altered State Machine) released NFTs infused with AI where you can take “the brain” (along with all the things it learned) and put it into another NFT, bot, or other digital entity.

- Moonsama – What started as a generative collection on Kusama and Moonriver, ended being a blue-chip project on the Polkadot ecosystem, with a Carnage event held in the Minecraft environment. While not technically a stand-alone game (yet), the creators are exploring the boundaries of the multiverse, blockchain gaming and NFTs.

Play to own

A type of play that refers mostly to user behaviour and the in-game assets. To be categorized as Play to Own, the assets have to fulfill two crucial conditions:

- The assets are NFTs (the standard may vary – from Kusama’s RMRK to Ethereum’s ERC-721, ERC-1155, and additional standards).

- The assets can be moved not only between the same series of games but carried between titles that originate from different franchises or companies.

Moving (or using) in-game assets to other titles, such as team members, has been around since early 80s. Games like Wizardry III: Legacy of Llylgamyn enabled the player to import party members from either of the two first entries in the series, Metal Gear Solid made use of game saves from other Konami titles (the developer of MGS) during one of the dialogues and Vib Ribbon made use of music CDs to generate levels. But these are the examples that dwell in the same ecosystem or hardware – Wizardry is the same gaming franchise, the original MGS uses game saves that come from games developed by Konami and Vib Ribbon makes use of the CD format that is not related to gaming. Of course there are always exceptions with Bard’s Tale enabling to import Ultima III and Wizardry characters but the result was rather disappointing and it was rather to lure the gamers that played other games than provide any significant benefit – no in-game easter eggs, no impact on the story. In this case, the promise of NFTs and blockchain is a lot more in terms of ownership and interoperability.

Play To Own puts an emphasis not only on a true ownership of the assets, but also on their interoperability between various titles not connected by a developer, a publisher or any gaming ecosystems. This is why (in theory at least), Play To Own should be strictly connected to Play To Earn, Play And Earn and Play to Experiment models and is non-existent in Traditional Gaming. Play to Experiment and Play To Own’s relationship can become one of the most intriguing branches in gaming, pushing the developers to aim higher in terms of game mechanics, quest creation asset and level design.

Examples could include:

- Sword that was acquired in Kingdom Hearts could be used in World Of Warcraft

- Splinterlands cards can be utilized in Gods Unchained

- An NFT medal / achievement for finishing CD Project RED’s Witcher 3 can give you benefits in Amazon’s New World.

This vision of interoperability is very utopian, almost impossible to achieve from the developers perspective (as noted by Rami Ismail in this great twitter thread) and would need to involve interdisciplinary teams, not mentioning the production costs. Even the projects that build on top of others (so-called Ectogames with the Loot initiative being the prominent example) stay in similar ecosystems for that reason.

Nevertheless, the interoperability factor is crucial for Play To Own as:

- Owning NFT items that can be possessed in just one title does not make them different from owning Fortnite skins, CS:GO assets or Team Fortress 2; items which are untransferable by design.

- When an NFT-based title shuts down the assets will be worthless, unless interoperability is introduced earlier or another entity decides to build upon them.

Even when we look at the number of mentions on NFT owning / interoperability on Google Trends, we can see the difference and see around what topics does the discussions centre the most, with ownership taking the lead:

This may be the result of the focus that the Web3 narrative puts on ownership, but the other side of that is the collectors’ spirit deeply rooted in the behaviour of the Treasure Hunter (both in gaming and digital assets collecting), a type of gamer that owns and grows their collection of valuables. If we refer to research papers such as the one from Jack Cleghorn and Mark D. Griffiths (both from Psychology Division Nottingham Trent University, UK) additional motives for buying virtual assets include item exclusivity, their function and the “cool factor”.

Examples for these kinds of games have yet to emerge but projects like Fragnova are working on empowering not only the sole ownership factor, but creating “on absolute interoperability of game data and logic, modable games and innovative creators UX” (as written by the creators).

Play to participate

This type of play puts an emphasis on pure engagement in gaming and participation in collective experiences. It involves both single player games (eg. Elden Ring, Final Fantasy series) and competitive / multiplayer games (eg. Street Fighter series, League Of Legends, Axie Infinity) – from both Traditional and Blockchain gaming.

Owning an asset (that can be obtained by playing the game or buying it) or/and playing to experiment are also a form of participation. It can be tied to an collective experience (eg. owning Wu-Tang Clan skins in Fortnite), community (like glitch hunters), guild (eg. YGG), gamified DeFi (DeFi Kingdoms) or fandom (eg. Metal Gear fanfiction writers ).

Play and experience

The state of play that includes all the models. One undertakes certain gaming titles for, enjoyment of the sprawling adventures and fantastical plots as Kurt Kalata wrote in “A Guide to Japanese Role-Playing Games”. Other players want to immerse themselves in the virtual world and detach themselves from reality.

For an additional crowd, monetary gain is the key to the best experience (as esports players, sellers of in-game items or Play and Earn beneficiaries). Experiencing gaming as a single player of part of multiplayer collective adventure is also a factor here as well as involvement from all player archetypes.

As we can observe, each State of Play does not threaten the existence of others – even when it comes to business models. Rather, each model influences and/or evolves over time, solving for prior issues or imperfections and building upon the solid fundamentals with a hint of experimentation, whether it is with game mechanics, graphics or economics.

Over the past decades, titles like WiBArM, Megami Tensei, Utopia and Space Panic have influenced gaming mechanics, UI/UX and even whole genres themselves.

Mainstream titles take bits of experimental breadcrumbs and put them into commercially successful products like Air Combat, Pokemon Red, Starcraft, World Of Warcraft, and Donkey Kong as some of the examples. Along with the mechanics and form experimentation, come various phases of in-game economy and currency which have had an extensive impact on traditional and blockchain gaming alike. With the rise of online gaming, we can also observe changing perceptions of in-game monetary assets – from being a mere indicator of digital points to becoming a backbone of virtual economies which can be exchanged into real currencies.

Rather than focusing on spreading FUD over NFT assets and blockchain gaming, fans of traditional gaming may want to divert attention to exploring new possibilities and aiding game developers with constructive feedback. Blockchain gamers and developers must work together to forge more sustainable economic systems, new game formats and user acquisition methods. Both sides, coated by Play To Experiment or Play and Experience, can provide guidance and creative stimulus for the mutual benefit of each other.