Jack Laing of Pocket Network defines governance in the context of Web3 simply as “rewriting contracts.” According to Mario Laul of Placeholder VC, decentralised network governance consists of 4 core components:

- Leadership, vision, and values that attract and guide network participants, i.e. deliberately putting emphasis on one or more of the following: decentralization, democracy, efficiency, etc.

- Rules inscribed in software, i.e. smart contracts, ability of the governance structure to update them, etc.

- Rules and regulations external to software, i.e. community precedents, nation-state regulatory environment, etc.

- Community coordination and management, i.e. community discussions, governance calls, etc.

A good decentralized governance structure aligns the interests of all stakeholders through a sufficiently flexible system of checks and balances, while offering enough space for leadership. Generally speaking, a good decentralised governance structure is one that:

- Steers the protocol through its various stages of development towards more innovative and socially useful functions.

- Resolves conflicts between different stakeholders participating in or affected by the network.

- Helps grow the protocol.

Imbalanced governance or inability to resolve conflicts between key stakeholders creates instability, which is particularly problematic for protocols positioned to become systemically important infrastructure with a large user base. The most important groups participating in token governance structures are:

- Technical Experts: Responsible for developing software and operating the relevant infrastructure (or otherwise contributing in a highly specialized capacity)

- Individuals / Organizations with large financial interests: Also referred to as “Whales”

- Ordinary Users

In practice, there is usually overlap between the three, but each of these groups is often associated with a particular form of decision-making:

- Technocratic decision-making: Experts

- Plutocratic decision-making: Whales

- Democratic decision-making: Ordinary Users

In their early stages of development, decentralised networks tend to be technocratic by default. For more inclusive decision-making, a typical next step is to implement a token-weighted voting system (i.e. voting power determined by the relative number of governance tokens used to express a particular preference), which usually results in plutocracy, as early stage investors and founders hold the majority of tokens.

Before projects can get to designing governance mechanisms, it is important to spec out the particular goals and values that will be guiding the governance processes, i.e. to what extent and at which stage the community should be involved, what the role of the founder / founding team should be in making decisions, at what stage should the founding team start removing themselves from governance, whether founding team’s power should be ingrained into the protocol.

It is important to note that in most cases, governance tokens are rarely pure governance tokens and usually have extra functionalities layered on top. Some of the examples of multiple functionality governance tokens include:

- Maker: The MKR governance token is not only used to vote on onchain governance proposals, but also serves as a source of recapitalisation when the Maker Protocol runs at a deficit, in which case the supply of MKR is diluted, to compensate for the deficit. The possibility of MKR token supply Dilution gives holders a strong incentive to govern the system well.

- Aave: The AAVE token holders can stake their AAVE token in the protocol Safety Module to help secure the protocol. If a shortfall event occurs, up to 30% of the stakes can be slashed to cover the deficit. In exchange for securing the protocol, stakers earn yield in the form of AAVE governance token.

- Uniswap: The most prominent feature is the option to earn pro rata trading fees from the Uniswap exchange, if UNI holders vote to approve this in the future.

Designing Governance Mechanisms

There are 5 key considerations to think about when designing a governance token or a governance structure:

- Scope: What are the key aspects of the token network that are governed by the governance structure?

- Mechanisms: How is governance practically exercised?

- Participation: How is efficient participation of the community members ensured?

- Decentralisation: How is the governance structure protected against plutocracy?

- Safety: How is the governance structure protected from malevolent actions? (e.g. flash loan governance attacks)

Scope

The first step is to determine what it is that the governance structure should govern. This is particularly important from the community perspective. The community should know from early on what parameters of the token network are governable, and that will help them form high quality opinions and help them engage with the network. Very project-dependent. To list a couple of examples, the main governable aspects in the top 3 DeFi protocols are:

- Maker: Collateral types; Vault types; Global system parameters; Vault-specific parameters; Replacing modular smart contracts

- Aave: Risk policies, monetary policies, improvement policies

- Uniswap: Protocol fee switch; UNI community treasury; uniswap.eth ENS name

If the scope of your governance is opaque and inconsistent, it is difficult for network participants to coordinate around a shared understanding of what is a legitimate course of action in different situations. That increases the likelihood of conflict, which can lead to fragmentation and network forks. Networks with governance models that are too complex or require excessive amounts of human effort or other resources tend to be less scalable and less adaptable. Some examples of instances when governance of a protocol failed include:

- The DAO Hack. Exploitation of a smart contract bug, resulting in imminent governance chaos, an Ethereum fork and creation of Ethereum Classic.

- NEM Foundation: Alleged mismanagement of treasury funds.

A good example of a well structured scope has been set by MakerDAO. It has introduced “Core Units” as a part of its process of complete decentralization as the Maker Foundation (original development team) dissolves itself. These units are responsible for certain tasks and they campaign for a quarterly/annual budget from MKR token holders. To date, there have been 5 Core Unit launch proposals.

- Growth: Responsible for growing the distribution channels for DAI with support and education for integration partners.

- Governance Alpha: Responsible for running the governance process for MakerDAO, including updating the MakerDAO governance portal with the latest information on new proposals.

- Smart Contracts: Development team extending the functionality of the protocol — currently focused on e.g. Layer 2 integrations.

- Real-World Finance: Integration of real-world assets as collateral to MakerDAO.

- Content Production: Responsible for the content on MakerDAO.com and the various social media channels.

Scope & Governance Minimisation

Fred Ehrsam, the co-founder of Coinbase, claims that most widely used protocols will trend towards what he calls governance minimisation, i.e. focusing only on the vital areas of governance where human input is absolutely necessary, such as:

- Treasury management. Governance of treasuries is likely required for the foreseeable future because deciding how to allocate funds is a hard problem to automate. Treasury management is not an automatable task, meaning people have to be in charge. Both Compound and Uniswap recently created grant programs for a portion of the protocol’s treasury to be invested in their respective ecosystems. The grant committees are teams of 5-10 people who allocate capital to improve tooling and complementary products.

- Complex parameter setting. As one example, Maker currently needs governance to approve new collateral types and set their corresponding collateral requirements. These functions are inherently hard to codify: the suitability and risk profile of a new collateral type (some of which may not even exist today!) is hard to assess in advance.

- Protocol upgrades.

The implementation of governance minimisation should in theory allow stakeholders to depend on a protocol, reducing the power of decentralized governance and reliance on decentralized governance wherever possible, ideally resulting in “credible neutrality”. Credible neutrality means that a stakeholder (e.g a user or a developer) can use or build on a protocol with confidence it will not change against their interests. Protocols remain credibly neutral by avoiding “capture” by any particular group. In practice today, governance minimisation most directly applies to minimising on-chain governance.

Outlining the scope of your governance structure early on is extremely important, because your stakeholders need to be aware of the various aspects of the protocol that they are required to provide their input for. It is also important to do proper contingency planning, as having an emergency plan helps with timely and efficient solving of the emergency. Last but not least, the scope should be divided into different units and individual team members should be directly responsible.

Mechanisms

In most cases, on-chain governance in Web3 protocols is exercised via voting, i.e. signalling support for a proposal using tokens. For example, a proposal to edit a smart contract of a DeFi protocol is automatically implemented if it reaches a sufficient number of “yes” votes in a period. Here the main considerations are the following:

1. Voting Mechanism: What should the actual Voting Mechanism look like? How are individual preferences accounted for and interpreted? There are 4 main types of voting mechanisms that we have identified:

a) Token-weighted voting: The strength of a signal is determined by the aggregate amount of tokens used by an address to back a proposal. If a voting address owns 10% of total supply of all the tokens, it has 10% of all the voting power.

b) Democratic voting: One person (address) equals one vote, which is arguably a more democratic approach. One example of an implementation is Pocket Network. Pocket airdropped voting rights to their community members, one vote per person. To qualify, community members had to go through a qualification process by playing their Metagame and complete certain quests in it. It provides resistance against whales and plutocracy, but requires a lot of community work to determine who should get a vote and presents a unique set of challenges around the fairness of determining who should get a vote.

c) Quadratic voting: Individuals get a certain number of votes per period and allocate votes to express the degree of their preferences across different proposals. Quadratic voting works by allowing users to “pay” for additional votes on a given matter to express their support for given issues more strongly, theoretically resulting in voting outcomes that are aligned with the highest willingness to pay outcome, rather than just the outcome preferred by the majority regardless of the intensity of individual preferences. However, the marginal cost of each additional vote increases linearly with the number of votes per the same proposal.

d) Conviction voting: Individuals express their preference continuously. The longer they keep their preference for the same proposal, the stronger their vote gets.

2. Quorum: What is the quorum required to pass proposals? There is no right approach and each approach has its pros and cons. Here is a couple of examples of how projects in the Web3 space solve this:

a) In Maker, voting is weighted by the amount of MKR tokens that vote for a proposal. For example, if 50 stakeholders hold a total of 600 MKR and vote for proposal A, while 100 stakeholders hold a total of 400 MKR and vote for proposal B, then Proposal A would win with 60% of the vote. Maker uses a mechanism called Continuous Approval Voting and the way it works is that your token vote is applied to one vote at a time. When voters vote on a new proposal, the MKR is removed from the old proposal, and the threshold needed to pass the new vote is lowered.

b) In Aave, the necessary quorum is not set in stone, but it is determined by the Genesis Team on an individual basis, based on the nature of the proposal, and this is possible because currently only the Genesis team of Aave has the ability to submit proposals on-chain. In Maker anyone can.

c) In Uniswap a proposal must achieve a quorum of at least 4% of all UNI (40M) voting for it. The purpose of the quorum is to ensure that the only measures that pass have adequate voter participation. Due to the higher initial supply and its lower circulation, it has become more challenging to meet the proposal submit requirements (10 million UNI) and achieve a quorum (40 million UNI) in governance. For this reason, delegation is more critical for Uniswap than for Compound, where one investor can decide almost everything. Only four addresses in Uniswap can submit a proposal compared to nine in Compound. The top 10 addresses by voting power, excluding the autonomous proposal, is also about 70%.

https://www.theblockcrypto.com/research/89964/defi-governance-games-curve-uniswap-1inch

3. On-chain vs. Off-chain Governance: How do on-chain vs. off-chain governance interplay? Off-chain governance includes uncoordinated individual actions, private conversations, public events, online interactions (especially on social media platforms where materials and memes are circulated), activities of various legal entities contributing to the network, or voting and decision-making mechanisms independent of on-chain governance. Again, there are no right approaches, a couple of examples below:

a) In Maker, there are Governance Polls that occur on-chain and are used to measure the sentiment of MKR voters. Executive Votes “execute” technical changes to the Maker Protocol. When active, each Executive Vote has a proposed set of changes being made on the Maker Protocol’s smart-contracts.

b) Aave uses a hybrid model, which means that community members can submit potential proposals on the Aave forum, and then other community members can express their opinions on these proposals. The Genesis team then takes the proposals that are perceived positively, turn them into Aave Improvement Proposals and submit them for voting.

c) Uniswap uses off-chain governance through gov.uniswap.org, which is a Discourse-hosted forum for governance-related discussion. Community members must register for an account before sharing or liking posts. New members are required to enter 4 topics and read 15 posts over the course of 10 minutes before they are permitted to post themselves. They also use Snapshot, which is a simple voting interface that allows users to signal sentiment off-chain.

https://gardens.substack.com/p/introducing-gardens

4. Delegation: Is delegation of token holders’ votes to another address allowed and encouraged?

a) Maker is considering delegation for the future.

b) In Aave and Uniswap delegation is possible.

c) Compound: Delegate votes from the sender to the delegatee. Users can delegate to 1 address at a time, and the number of votes added to the delegatee’s vote count is equivalent to the balance of COMP in the user’s account. Votes are delegated from the current block and onward, until the sender delegates again, or transfers their COMP. Addresses delegated at least 100,000 COMP can create governance proposals; any address can lock 100 COMP to create an Autonomous Proposal, which becomes a governance proposal after being delegated 100,000 COMP.

5. Token Lockup: Do voters need to lock tokens into smart contracts in order to vote?

a) Maker requires voters to send MKR tokens to a voting contract.

b) Aave and Uniswap do not require voters to stake tokens in order for them to vote, voters only need to have them in your wallet.

6. Time Considerations: How long does the vote last for?

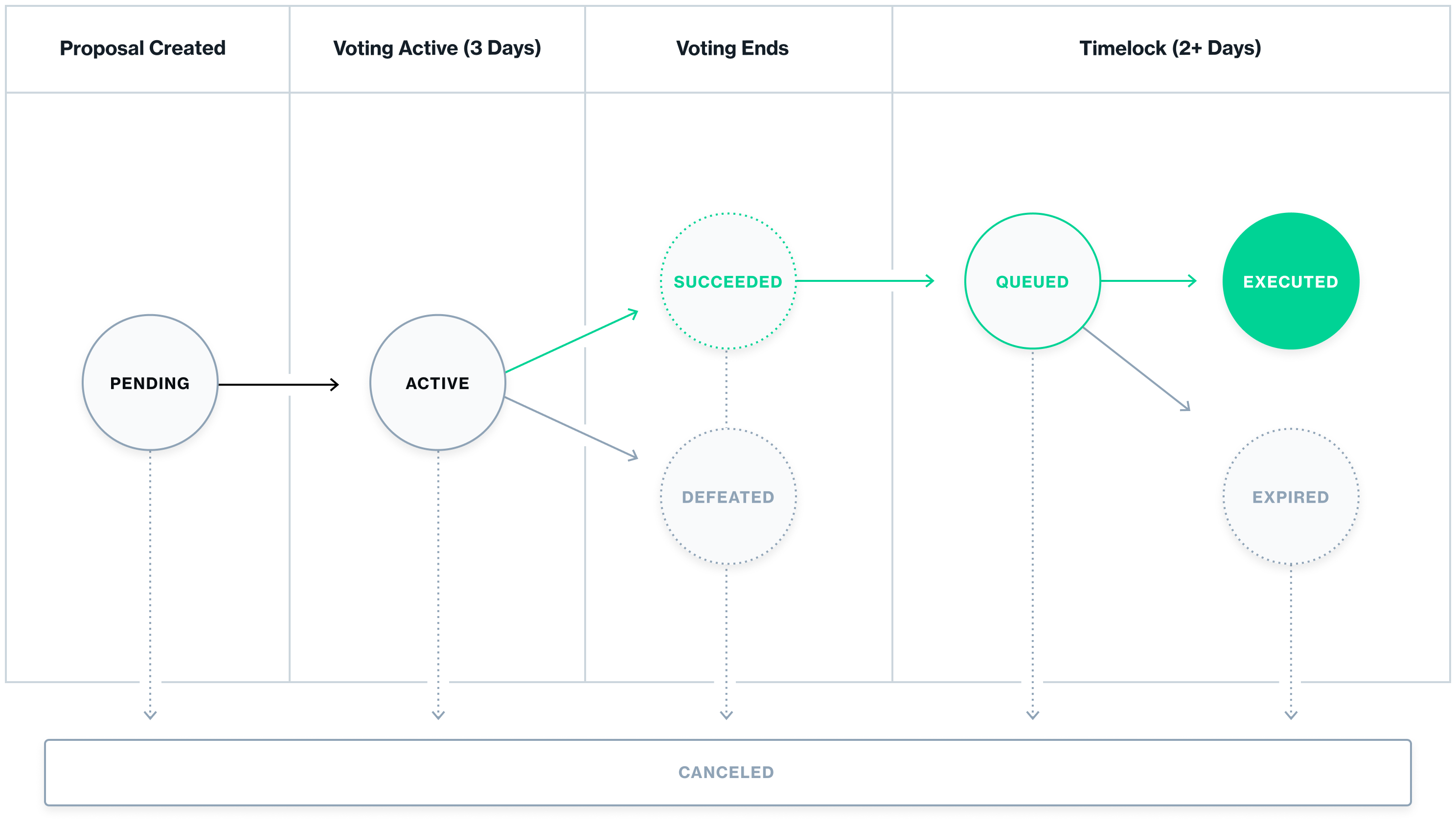

COMP token-holders can delegate their voting rights to themselves, or an address of their choice. When a governance proposal is created, it enters a 2 day review period, after which voting weights are recorded and voting begins. Voting lasts for 3 days; if a majority, and at least 400,000 votes are cast for the proposal, it is queued in the Timelock, and can be implemented 2 days later. In total, any change to the protocol takes at least one week.

Mechanisms – Governance mechanisms on demand

There are a handful of existing turnkey blockchain governance solutions with mechanisms that can be easily implemented by any crypto protocol:

- Aragon: The Aragon Network is an Ethereum-based protocol whose mission is to give internet communities “unprecedented power to organize around shared values and resources.” Aragon is a set of smart contract templates, which can be used as the basis for organization, decentralized decision making, money management and dispute resolution. There are currently ca. 1,700 decentralized organizations, and Aragon DAOs cover ca. 90% of their total assets under management, which makes Aragon

- DAOStack: DAOstack is an Ethereum-based open-source software stack designed to support a global collaborative network. The stack can be used to build organizations for any kind of collective work, and it also contains tools to link these organizations together, so as the network grows, all its member organizations are strengthened. DAOStack is currently the 2nd most popular choice, after Aragon.

Governance mechanisms are the cogs of the governance structure. Although there are many approaches to voting mechanisms, quorums and the interplay of the on-chain and off-chain governance, it is important to bear in mind the specificities of your project when making these decisions. It is generally advised to allow for delegation, as that enables better informed stakeholders to have more weight in decision making. It is also advised that projects should not require voters to lock up tokens, as that creates unnecessary friction in the voting process.

https://medium.com/daostack/an-explanation-of-daostack-in-fairly-simple-terms-1956e26b374

Participation

Another key consideration is how to incentivise participation in governance processes. Participation rates tend to be low and voters’ apathy is present. There has been a lot of criticism of MakerDAO governance for being centralized and passive (a16z owns 6% of MKR tokens and has not been participating in the governance processes). It is likely that Maker’s governance solutions are unpopular due to the requirement to lock tokens and the lack of a delegation function. Participation rate can be low due to multiple reasons, some of which are listed below:

- High financial costs of voting: Ethereum gas price leads to a decrease in governance participation due to the need to pay more than $5 per transaction. The infrastructure for gasless voting solutions using EIP-712 signatures is very new.

- High complexity: The MKR governance token allows for changing the economic rules of the Maker Protocol. The parameter changes are aimed at helping to preserve the DAI peg to $1 and increase its supply while minimizing a system crash risk. However, understanding these considerations requires a substantial amount of research.

There are certain actions that can be taken to mitigate the above-mentioned problems:

1. Off-chain voting to address the high cost of voting:

a) Snapshot: The most commonly used framework for off-chain voting. 349 Ethereum projects use it for governance, such as SushiSwap, Yam, Cream, Compound or Uniswap.

b) EIP-172: A proposal introducing on-chain gasless voting.

2. Delegation of votes to address high complexity: Delegation of voting power to entities that are better positioned to make a good decision is a possible solution. However, this approach probably works better for a small number of poll options, e.g. in Compound governance. Otherwise it is much more likely that the delegate expresses an opinion not consistent with the opinion of the token owner.

3. Maintaining lively forums to address voters apathy: Having a public forum allows the community to suggest an idea or a change for a protocol parameter and ensure that this proposal is supported. After creating a topic on a forum or signal voting, a proposal creator can submit it on the blockchain. The proposal then undergoes a formal procedure for collecting votes from the governance token holders. It is also important to organize regular governance calls and keep voting times regular and periodic, which gives the community a sense of order and rhythm.

The core thing to do to increase participation rates is to remove frictions in participation. Good governance processes and tooling are the most important considerations here.

Decentralization

One of the key aspects of a well-functioning governance structure is decentralization, i.e. relatively even distribution of voting power among a large number of participants. In other words, protocols should ensure that they are not governed by large players only or prevent a single active large token holder from dominating the governance process entirely. For example, SushiSwap’s proposed Solana deployment and liquidity incentive program is largely driven by FTX’s Sam Bankman-Fried, who has the power to push such proposals through with his large SUSHI holdings.

Decentralization is not a binary state, not a destination but a process in the lifetime of a protocol. There are 2 ways of approaching decentralization:

- Progressive decentralization: A framework for approaching decentralization in early-stage startups by Jesse Walden (then a16z). Progressive decentralization prioritizes product-market fit and community participation over decentralization and claims that the team needs to stay in control of the protocol in order to move fast. Only after product-market fit and community participation have been achieved on a sufficient level should the team hand over control to the community.

- Community-based decentralization: A framework created in opposition to progressive decentralization by Sacha Saint-Leger. Community-based decentralization states that a “fiercely loyal community” comes above product-market fit and that in order to create such a community, teams need to hand over control to the community relatively early.

There is no right approach to decentralization of governance. However, most projects have been taking the path of progressive decentralization and it is still the approach we would advise to take, as it allows founders to make quick decisions that would be almost impossible to make in a totally decentralized protocol. It is of course still very important to make the community feel that they are a part of the decision making process and that their opinions are valued.

Safety

Resistance to exploitations is one of the key considerations when designing a crypto protocol and governance mechanisms constitute yet another attack vector that teams need to be aware of. One of the main ways to exploit a protocol via its governance structure are flash loan governance attacks.

At the end of October 2020, a project called BProtocol leveraged a flash loan in order to influence a Maker governance vote. The question is how to ensure safety of governance mechanisms? There are a couple of things that can be done:

- Increase participation rates in governance processes: Low voter participation rate makes attacking crypto protocols cheaper. For example, a malicious actor taking a short position and borrowing e.g. MKR to push through a proposal that destroys the system.

- Make users lock tokens into the protocol: For example Maker’s MIP49 staking rewards: MIP49 proposes that a portion of the fees will be distributed to MKR token holders who stake their tokens. The idea behind the proposal is to encourage locking tokens — currently suggested at 2 weeks — to take them off the lending market. Borrowed MKR tokens that participate in governance can be used to launch attacks, as we have seen with BProtocol’s actions last October, and taking supply off the market makes that more difficult. Locked tokens also pay lower gas fees when participating in MakerDAO’s governance process.

Conclusion

Designing a good governance token is extremely difficult, but there are a couple of proven approaches that you can do:

- Outline the scope of your governance structure early.

- Plan for contingencies and how you will use governance to resolve them.

- Divide the governance scope into different units and make individual team members responsible.

- Allow for delegation of votes, as that enables better informed stakeholders to have more weight in decision making.

- Do not require voters to lock up tokens, as that creates unnecessary friction in the voting process.

- Remove friction in participation to increase participation rates.

- Take the path of progressive decentralization to make quick decisions that can ensure survival of your protocol in its early stages.

- Increase participation rates in voting processes to improve the safety of your protocol.